“Over time, it became clear to me that there’s a problem with the question ‘What can I do.’ The problem is the word ‘I.’ By ourselves, there’s not much we can do… The right question is ‘What can we do to make a difference?’ Because if individual action can’t alter the momentum of global warming, movements may still do the trick. Movements are how people organize themselves to gain power—enough power, in this case, to perhaps overcome the financial might of the fossil fuel industry… Movements are what take 5 or 10 percent of people and make them decisive—because in a world where apathy rules, five or ten percent is an enormous number.” ~Bill McKibben (“The Question I Get Asked the Most“)

I recently saw a new post by Carol Horton, the second in a series on Yoga International called “Re-imagining Yoga: Holistic Wellness, Social Connection, and Spiritual Revitalization.” In the most recent post on Spirituality & Social Justice, she describes what she called the experience and rise of what she terms “socially engaged spirituality.” I’ve been sitting with her words for several days now thinking about this “re-imagining” of the practice, and for a number of reasons it just hasn’t been sitting well with me. I want to talk about why.

Horton introduces the experience of “socially engaged spirituality” by sharing a story of her youth when, in the first grade, her class was brought into a gymnasium to hold hands and sing together a freedom anthem of the civil rights movement, “We Shall Overcome.” It’s a lovely tale, and one she argues embodies the hopeful, spiritual possibility she feels may be developing in some yoga circles, particularly in the yoga service field, described as “people who have launched successful organizations dedicated to teaching yoga in prisons, supporting recovery from addiction, and so on.”

I agree that the growing awareness in yoga circles of social justice concerns is promising. It is wonderful to see so many people “seeking to deepen their practice by engaging more deliberately with the world—rather than escaping, renouncing, or transcending it.” As she mentions, “to see this happening on the scale that it is today… is unprecedented.” This is something to be hopeful about, and I am happy this conversation and service work is growing. As McKibben notes, “It’s the right question or almost: It implies an eagerness to act and action is what we need.”

But while I applaud those engaging in yoga service I also feel that service work in yoga is something we need to be critical of, for a number of reasons. As I have written about before, there are often problematic elements to the organizational structures of groups involved in the yoga service field (often through no fault of their own). The nature of the industry is often not set up to support more radical approaches than what Horton I think appropriately calls a “socially engaged spirituality,” as the model of the industry is often based on a form of charity work driven by white middle-class communities, in ways that are rooted in the colonialist history of philanthropy within the construction of the United States, rather than more radical, overtly political models.

I do want to acknowledge there are groups of socially engaged spiritual yogis out there doing political, activist work and engaging in social justice beyond the mat. You do exist, and I commend you. Just to clarify, this post isn’t about these people, who I think are creative and bold individuals (those of you doing this type of work know that you can often be treated with disdain or virulent sanctioning by those in the yoga world who find this work “unyogic” and “judgemental” because of the political bent). More importantly, I think it’s important to recognize that while many yogis want to believe they are socially engaged in radical ways, these people are rare in the yoga world, even in the yoga service world, in part because mainstream yoga often promotes a more individualized, complacent positivity that is constructed as at odds with political engagement.

This post addresses the majority of service work in yoga that is not overtly political, that is not seeking to engage in collaborative movement building and organizing both within but also outside yoga circles, and which often uses a “socially engaged spirituality” to justify their own personal commitment to social justice without engaging in actions that are radical enough to promote more effective and widespread change beyond the individual level. To those folks, please listen, and I hope you take this post as a plea to think deeper about what social justice means and why spiritually informed social engagement demands an active, political, and collaborative approach.

The Dangers of a “Socially Engaged Spirituality”

What exactly does it mean to have a “socially engaged spirituality”? Who does it serve? What type of social engagement does it enable? Why is yoga service becoming more popular, and can we problematize this sociohistorical context?

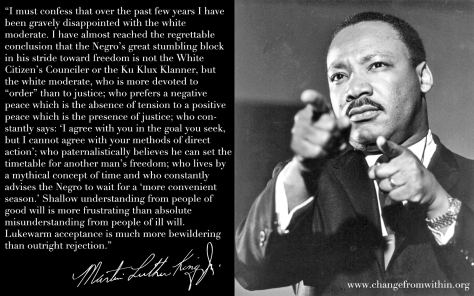

Horton’s construction of a “socially engaged spirituality” is one that is deeply personal, and as such is very focused on the “I” question: “what can I do?” rather than the question “what can we do?” And this is particularly interesting given that the civil rights movement she cites in her original story of her six year old self holding hands and singing “We Shall Overcome” was driven by a powerful religious tradition and social network; in other words, it was a movement based on the question of what we could do, not what I could do. Churches and church networks were central in the success and spread of the civil rights movement. The movement Horton so romantically recalls in her post ultimately was one that (while diverse and sometimes conflicted) was able to come together in unity and purpose to accomplish great change, and it did so through loosely coordinated efforts on the part of movement organizers/organizations, which included on the ground activism, not just unifying sing-a-longs–though these are of course nice too. When we focus on a personal form of “socially engaged spirituality,” we can miss the potential for unified resistance, for unified transformation that the civil rights movement embodied.

My worry in the type of approach Horton uses in the re-imagining of yoga is that even while expanding a personal spirituality to include social engagement, because the nature of this engagement is not clear it’s incredibly easy to fall into the trap of ego, self-service, and privilege in application. Meaning: when our spirituality is socially engaged only on our own terms, and in ways that are geared toward meeting the needs of the one doing the service rather than the populations that service addresses, and without broader political understandings and engagement in unified social movements or activism, ultimately the transformative potential of service work is significantly lessened and, potentially, even utterly destroyed. Sometimes, service work (if done in ways that aren’t rooted in deep understanding) can actually lead to the supporting of systems of the very oppression such service advertises to fight or solve. As Uma Dinsmore Tuli has said, “Yoga is a toolkit for liberation often used in the service of oppression.”

The danger of reproducing inequality in service work isn’t necessarily a surprise when we consider who is often involved in these types of service organizations. As most people know, yoga practitioners in the USA and Western countries are often a narrow demographic group: predominantly middle- to upper-class, highly educated, and majority white. In other words, many people getting involved in these projects are privileged, and may not have first hand experience or even adequate educational knowledge to understand the types of work they are engaging in. In my own research I have heard of numerous cases where the people running these organizations know very little about the populations they are serving, and don’t have adequate training to safely and effectively serve those most at-risk (here’s one example for you). Yogis are not required to receive even basic diversity training in their certification programs. This can often lead to forms of service that are not coming from a place of knowledge, that are not actually beneficial to the communities served in the long-run, but often just bolsters the legitimacy of those engaging in the service work and teaching the classes, and props up an unsustainable and harmful system in need of drastic reform.

The tendency in the West is to individualize service work. It becomes something an individual does, or an individual organization, perhaps (as I have said before), an excuse to mitigate personal feelings of guilt for those with privilege, as a way of easing our own self-doubt and insecurities, and as a way of healing ourselves rather than a means of truly serving other people. This is largely because yoga, and yoga philosophy, is interpreted by Westerners through our capitalist, individualist, and neoliberal ideologies in ways that appropriate the ethically guided spiritual practice of yoga out of context of the profound understanding that comes through absorption with the object of our focus and meditation. It becomes a project one either succeeds or fails at independently, in relative isolation. But in isolation, we have significantly less power.

The growing trend of yoga service also often only involves the teaching of asana/postural yoga classes to at risk-populations. Don’t get me wrong, there is definitely value gained by these populations through these types of class offerings! But the idea that a postural yoga class or two can somehow solve larger systemic problems is flawed logic. It is essentially a stop-gap measure; it does not cure the underlying illness, despite lessening the impact of the symptoms of disease (somewhat). Instead of listening to what the populations we serve actually need, we listen to ourselves and serve them in ways we believe (or want to believe) are beneficial. We volunteer in prisons, rather than fighting and advocating for a better system that won’t imprison so many people in the first place. We provide asana classes to poor youth (often of color), rather than addressing the underlying issues of poverty, segregation, crime, unequal education, and limited job opportunities they often deal with. Instead of engaging in advocacy, activism, and movement organizing, we engage in attempting to promote personal self-care within a system that is slowly killing us. We become complacent, and complicit, rather than resistant.

In this way yoga service can often take the form of a white savior complex, a trend where whites increasingly use service work (and charitable giving) as a means to justify and validate their own unwarranted privilege, thereby reinforcing it, rather than actually performing service in the interests and according to the needs of the ones they serve to disrupt unequal and intersectional systems of oppression/privilege. Thus, the white savior supports brutal policies in the morning, founds charities in the afternoon, and receives awards in the evening. As Cole says, “there is much more to doing good work than ‘making a difference.’ There is the principle of first do no harm [ahimsa!]. There is the idea that those who are being helped ought to be consulted over the matters that concern them.”

All agree that in the last five years, there has been an exponential expansion of this sort of work, particularly in the U.S. Interest in integrating yoga practices into major public institutions, as well as in fields such as education, criminal justice, public health, social work, and psychotherapy is vastly higher than it’s ever been before. All evidence suggests that the growth of socially engaged yoga will continue to snowball in coming years. (Carol Horton, “Re-imagining Yoga, Part 2: Spirituality and Social Justice”)

One of the reasons there has been such an exponential expansion of this sort of service work is that the yoga industry has been pumping out new teachers in recent years, and one of the ways these teachers are often encouraged to gain experience is by engaging in “service work,” aka, teaching free classes so they can further their career goals. It seems radical, and progressive, and yogic (seva!), but often in reality free classes are just as much about serving the needs of the teacher as they are about serving the needs of their students, and in many ways are more focused on the needs of the teacher as they don’t always even engage in dialogue with the populations they serve. I have heard countless teachers encourage new students to teach for free, to do charity work and classes as a means of gaining experience (with the implication that the end goal is primarily to, upon gaining more experience, teach to a wealthier clientele who can afford to pay).

The growth in yoga service work has also been enabled by the continuing defunding and gutting of social welfare systems in the USA, combined with a stagnating middle class, unlivable minimum wage, and growing job insecurity that means this type of charity work in some ways becomes a means of supplementing the growing scarcity of government funded programs and support networks that leave so many populations at risk. The problem with this is that charity work is often unable to adequately fill these gaps, and as we know historically and even today of charity work, there are often disparities within aide or required stipulations on who is able to gain access to such aide that can be problematic. (For an excellent exploration of why doing “good work” doesn’t always mean we are “good people”, see this post from Michael Lee via the Huff Post.)

And finally, this is exacerbated by the fact that many teachers are limited by the expectations of their professions to present an overly positive (cult of positivity, anyone?) outlook, which typically means that political discussions are considered “unyogic.” People who engage in critical discussions and political activism in the yoga world are often seen as “focusing too much on the negative.” This limits the type of engagement yoga service workers can sometimes practice, provided they want to be seen as “authentically” yogic and to retain or grow a following within the yoga world more broadly. This is something more yoga teachers need to be willing, and able, to push back against, because ultimately a deep understanding of the world and our locations in it per a yogic practice intent on uncovering bias and living ethically requires a recognition that the personal is inherently political, and that there is no yogically sound way to engage in a “socially engaged spirituality” without also being political.

Re-Imagining Yoga: “Spiritually Engaged Activism”

“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” – Martin Luther King, Jr.

If we truly want to engage in re-imaging the intersections of spirituality and social justice we have to take our spiritual understanding of the practice beyond a potentially self-focused “socially engaged spirituality” and instead begin to form a collective movement for “spiritually engaged activism,” where spirituality guides, informs, and even necessitates the development of a unified, intersectional movement predicated on a spiritual understanding of ethics and morality.

We need to begin thinking about how we can unify spiritually in ways that create social engagement that is inherently radical, political, and intersectional. We need to think about how we can strategize beyond just the individual level, beyond individualism, to develop a sense of collectivity and unity even as we acknowledge difference. We need to stop modeling ourselves on the current models of white charity predicated in histories of the “white man’s burden” and colonial missionizing narratives. Instead I think we should consider how we can decolonize service work, gaining inspiration from the radical potential of groups like, for example, the black panther movement, which fed millions of children through their free breakfast program while raising awareness on the racial inequalities of food scarcity in the USA.

We need to think about how we can model ourselves on movements like the ongoing indigenous resistance to climate change, environmental racism, and corporate power that seeks to ground their resistance in spiritual traditions and experiences shared by hundreds of indigenous tribal peoples across the Americas.

These types of movements are rooted in a deep spirituality and social engagement with the world as it is (not as we would like or romanticize it to be). These movements don’t just close us off from connection, or prescribe an individual level of healing that never quite heals us completely; they open us up to building communities of activists, allies, and protectors that can provide mutual support and connection. They allow us to heal at the communal level, to heal in ways that get to the root of our insecurities and trauma both as oppressors and as oppressed peoples, because ultimately in systems of oppression, everyone suffers. The spiritually engaged activism these groups engage in is just that: action, organizing, and resistance that goes beyond treating symptoms of a larger disease and instead seek to overcome and cure the actual illness.

Perhaps, rather than solely focusing on the individual healing we can gain from a “socially engaged spirituality,” we can ask: How do we use a yogically informed spirituality to engage in intersectional movement building and support systems? How can we cultivate an intersectional, “spiritually engaged activism” rooted in yogic philosophy and practice? And how can we achieve this together? Is the model for yoga service currently gaining popularity simply not enough, and how can we radicalize it and decolonize it to be more effective in promoting industry and government changes that ensure greater equity and social justice for everyone?

Some Additional Resources:

[i] “The Black Panthers: Revolutionaries, Free Breakfast Pioneers” by the National Geographic

[ii] “End of the Line: The Women of Standing Rock” via Ic Magazine

[iii] “Just Because You Do ‘Good’ Work Doesn’t Mean You’re a Good Person” by Michael Lee

Hi Amara –

I’m afraid that you completely missed the central point of my article, which is that I am interested in yoga and related practices that **integrate** individual and social change, not individualized forms of charity work and personal spirituality. I think this dual emphasis is a much-needed corrective to the sort of non-self reflective activism that regularly produces burnout and/or self-righteous “holier than thou” Leftist “savior complexes” (speaking of). Of course, this line of thinking is by no means exclusively my own, or even that of socially engaged yoga world. Rather, it is part of an emerging Zeitgeist that is evident in quite a few progressive activist circles today, as well as a few pockets of the yoga world.

As far as how to do this work better, I’d encourage you to submit a proposal to present a workshop at the next Yoga Service Conference, which is held every May at the Omega Institute. Contrary to your assumptions, there is actually quite a lot of interest in integrating yoga service and social justice work, and the conversation and collaboration in that regard is ongoing. We’d love to have you become a part of it.

As for a more in-depth take on my views on civil rights and related issues, I encourage you to read my book, “Race and the Making of American Liberalism,” which was published by Oxford University Press in 2005. In fact, I have an entire chapter analyzing the civil rights movement there that would enable you to put the little anecdote that I used in that Yoga International article in a bigger context. Once you’ve read that, I’d love to hear your further thoughts!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Carol, thanks for the clarification! I definitely realize that a short blog post isn’t enough space to get into these topics deeply (my post as well!), and as I said, I think the trends in the yoga world that you point to are very promising. I just think we need to be mindful and critical too.

I’ve been wanting to come to the Yoga Service Council for years now but it’s just so far for me from CA, and funding to travel is a bit tough as I can’t get funding for that type of conference through my program (not academic enough, sigh, oh academia!). From your past reviews of the conference I think the people who are drawn to it are probably many of the most social justice minded and politically active folks in the yoga world today. With that said, I do think there are many other people in yoga engaging in “yoga service” that aren’t as politically minded and engaged, which is more what I was talking about. Sorry if that didn’t come across as clearly.

And I will definitely check out your book! I’m familiar with some your other work but not that one yet. Sounds fascinating.

LikeLike