When I first got into graduate school, I was warned that degree programs were designed to break you down and build you back up again in the University’s own image, in what we might call normative ways. Graduate school is ultimately a ritual transformation, a rite of passage and initiation, marking a person’s transition from one status to another. The question is–what is graduate school transforming us into?

The past year has been one of intense change for me and my family. I am happy to report that I finally finished my Ph.D. in Sociology in Fall 2018 (the one year anniversary since I filed will be December 21!). For those interested in my research, my dissertation is now available on ProQuest. With that said, I’d encourage folks who want to read my work on yoga to wait a bit longer. ProQuest can be expensive depending on what library access you have and I am planning on submitting a book manuscript draft to academic presses soon. There are some important post/colonial elements I had to cut for the dissertation that will be included in the book that I think are worth waiting for.

The other big news I have to share is that at the same time that I was finishing my dissertation, I went on the job market (for the second year). Somehow the stars aligned because I landed a tenure-track position as an Assistant Professor specializing in Popular Culture at California State University East Bay. So this Fall 2020 I started my new job and my partner, my dogs, and I moved to the Bay Area.

I have been meaning to write a post about this huge milestone and transition for a long time. To be honest, the draft of this blog has been sitting, collecting dust, for many months. The whole process of finishing my degree and job hunting was difficult and draining, making it hard to come back to. With that said, it has also been an exciting and joyous time. As the wheel turns and we are nearing the end of 2019 and the beginning of 2020, I want to share some reflections on graduate school and academia.

This post isn’t part of the trend of “quit lit” that has become pervasive in higher education, since I’m not leaving the field. It is, however, a critical reflection on my own experiences as a graduate student and now new Assistant Professor. In this sense, it’s a response to historian Erin Bartram’s powerful piece “The Sublimated Grief of the Left Behind,” where she challenges “academics — especially those who have landed coveted tenure-track positions — [to] take a minute to think of the all their colleagues who have been ‘lost’ along the way” (as quoted in Flaherty 2018). According to Bartram, “those left behind, or, as we usually think of them, those who ‘succeeded’, don’t often write about what it means to lose friends and colleagues,” allowing academia to avoid grappling with the loss and grief of seeing so many of our peers quit working in higher education.

As one of those rare folks who managed to land a tenure track job, it’s been a strange and complex experience to process the change occurring in my own life–especially since I still have close ties to so many friends who are amazing scholars currently navigating the job market or who have been pushed out of academia over the past few years. I also want to strongly resist language that paints this as their “choice” to leave, given it’s overwhelmingly due to structural and cultural norms that rely on pushing out a large percentage of graduate students after exploiting them as cheap adjunct labor or funneling them into precarious lecturing positions.

After accepting my new position at CSUEB, I struggled with “survivor’s guilt” for months, ironically feeling imposter syndrome more intensely after finishing my degree and landing “the dream job.” I don’t know if it’s possible to ever fully overcome those feelings of being an imposter or somehow being undeserving of my new position. I also don’t know if completely overcoming those feelings is something to strive for, since that vulnerability and anxiety can be an important source of empathy and humility.

After reflecting on my graduate school and job hunt experiences, there are a number of things I wish I had realized sooner in my graduate studies. I have written them down here as a means of processing my own thoughts and with the hope that this exploration is helpful for others.

Graduate School As Colonizing Technology

“Making ‘good’ citizens was as much about excluding or subordinating certain kinds of people as it was about including, regenerating, and reshaping others…. Schools forged disparate paths to citizenship… that frequently precipitated and overlapped with constructions of race and nationality. In this sense, schools within the bounded national space often served as domestic colonial institutions, espoused narratives that projected American power onto other foreign and domestic geographies and populations, and created distinctive paths to citizenship that many native-born and indeed many naturalized whites hoped would strengthen the boundaries of race and nation…. Rather than treat colonialism as a process tangential to or apart from public schooling in the US, it needs to be understood as a central ideological, narrative, and organizational force in schools.” (Clif Stratton, Education for Empire pg. 3,7)

For most of my time as a student, I didn’t think critically about schools, their origins, their purpose, and the inequality built into educational institutions. I was aware that schools were characterized by inequality, but it wasn’t until I got into higher education and the University of California system that I began to learn substantially more about how deep and pervasive it is–it’s worth noting a lot of what I learned was actually through activists fighting tuition hikes. This experience undoubtedly reflects my own privilege within educational institutions, but I also think it relates to the way schools are often hailed in the media as a great equalizer, as a source of meritocratic value and as an “objective” and normal part of life for most children (up through high school) and many young adults in the US today (for college).

During my time as a graduate student, lecturer, and now tenure-track faculty member, I’ve learned more about the inequities, conflicts, and politics of higher education than I’ve honestly ever wanted to know. And the more I’ve learned, the more I’m convinced that there are a whole mess of problems within academia and the graduate school system that are rarely discussed or brought to light.

This is old news, of course, so I’m not trying to claim this is some sort of insight of my own. My views on education systems have been informed by radical activism such as the Third World Liberation Front strikes and recent struggles around the adoption of Ethnic Studies curriculum, as well as scholarly research in critical race theory, Marxist traditions, feminist research on professions, and post/colonial work on the origins of educational institutions and (forced) cultural assimilation of indigenous people. I consider these various sources to be part of a “critical university studies,” which includes recent books like The Imperial University (2014), Decolonizing the University (2018), and la paperson’s (2017) A Third University Is Possible (you can also check out the Radical History Review’s online micro-syllabus).

We are often encouraged to gloss over the more unsavory aspects of graduate school when talking to prospective students or the general public in an attempt to lend our profession more legitimacy and prestige, and ultimately to give more (positive) purpose to our own lives and experiences. But it’s essential to recognize how the University operates to police and contain difference and what this means for graduate students, particularly those most marginalized and/or targeted within education systems. Because let’s face it, graduate school is hard. It’s designed to be. And I wish more people talked about it and warned potential new students about the difficulties they may face while pursuing a graduate degree, particularly if you are an activist-scholar. How else can we give consent to enter into graduate programs unless we aren adequately informed about the nature of University systems or the experiences we are likely to face as students?

According to la paperson (2017:2), colonialism consists of a set of “technologies of alienation, separation, [and] conversion of land into property and of people into targets of subjection.” By doing so, the process remakes not only territories but also views indigenous and marginalized bodies (and minds) as natural resources to be exploited. Resulting in radical social and cultural ruptures, technologies of colonialism are designed to create and maintain new patterns of relationships with the spiritual, with the world, with temporalities, with language, with social divisions, and within the psyches of all involved (Fanon 1963; Memmi 1967).

University systems are one such colonial technology. Most American universities are built on unceded indigenous territories and were designed to educate a particular type of student: young, rich, white men. These men’s educational journeys were meant to produce a particular type of citizen, one who believed in projects of empire as well as the inherent good of the nation state and who could pursue their studies largely because of the continued unpaid domestic and care labor of women. The modern University is, unfortunately, still largely predicated on this model of an ideal student who does not have to work, does not have care obligations, and whose studies contribute to nation-building activities.

University spaces (especially graduate programs) are meant to transform students into “valuable” and “productive” members of society and often perpetuate particular social and cultural paradigms rooted in existing systems of inequality. Some programs are more creative, innovative, or critical than others depending on the field of study. But generally, the purpose of schools is to socialize students into ideological belief systems in ways that serve the interests of a white settler colonial state. In doing so, schools alienate, separate, and sort students according to a host of variables, treating them like exploitable resources. Historically, individuals from marginalized groups who entered into University spaces were generally included in so far as they adopt the Eurocentric and patriarchal norms of such institutions, in so far as such bodies could be made legible and liable to such institutions (see, for example, Carter Woodson’s 1933 foundational work The Mis-Education of the Negro).

Graduate school, especially Ph.D. programs, can heighten these forces of control and socialization given such programs are professional entry points into University careers. Graduate programs are often designed to be intense experiences and are characterized by overwork as well as high rates of stress, anxiety and depression among students (especially among the social sciences/humanities). Drop out rates in Ph.D. programs are ridiculously high, often estimated to be around 50%. The academic job market, where such grad students are theoretically meant to move on to full-time, tenure-track positions, is so competitive and emotionally intense it’s often described as a “nightmare” and has even been compared to a drug gang. The program is literally designed to break us down and build us back up again, in the University’s image.

Part of the resocialization that is forced upon us in graduate school is made possible by the way such programs isolate students. Ph.D. programs rely on students traveling to new areas, often geographically isolating them from their local communities. Specialization in programs is designed to compartmentalize us into fields, and often discourages interdisciplinary work given the structure of program milestones. In this sense, programs often seek to divide and classify and separate us, even as they teach us “appropriate” ways to go about data gathering and analysis designed to promote “objectivity,” a goal that has been heavily critiqued among feminist scholars (particularly through standpoint theory and feminist science and technology studies). Programs, especially R-1 programs, and the publishing industry in academia often end up suppressing radical thought and critical voices, discouraging public sociology that has too much of an “activist” bent.

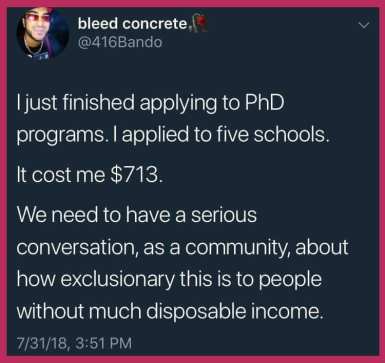

For example, let’s look more closely at the career pathway of faculty into academia. Ph.D. programs often necessitate moving away from local communities, not to mention the inequity built into applications, which can be incredibly expensive and prohibitive for students traditionally marginalized from educational systems (especially those who are poor, people of color, disabled, or sexual or gender minorities).

The more presitigious the institution, the more likely the students at that school have moved to attend. This can make it more difficult for students to form long-lasting connections to local issues, and the heightened pressure on students who want to land jobs at prestigious schools can also make it challenging to find time for alternative types of work or more creative or critical research. To achieve tenure track positions, you have to be willing to uproot yourself and move again, perhaps multiple times, in ways that are disruptive and prevent establishing strong community roots. Does this always happen? No, of course not. Department and administrative politics will influence how receptive a school is to local candidates. But the higher up you go toward R-1 schools, the more competitive and the more unlikely they can be to hiring local applicants (from what I’ve seen).

Since Universities are a colonizing technology, it can be difficult to resist the resocializing impacts of such graduate programs. They are designed to isolate us, disconnect us from local struggles, and ensure the exclusivity and legitimacy of higher education is maintained.

With all this said, I recognize that there can be immense benefits of education (more to come on this), so University systems are inherently contradictory and complex. However, I think it’s important to acknowledge that University spaces reflect unequal power relationships rooted in incredibly racist, colonist, and classist histories (as well as religiously biased!) and are invested in their continued replication. As such, they can be toxic and harmful spaces for many people. This is often heightened in Ph.D. programs given the way that academic professions rely on such spaces to sustain themselves across time, not just in terms of producing new faculty candidates but in maintaining a system of precarious adjuncts who take on a large proportion of teaching responsibilities at educational institutions.

As a result, to survive, let alone thrive in such programs while maintaining a revolutionary ethic takes strategy and support, and sometimes a lot of luck or unfortunately a lot of privilege.

But… Universities Can Be Liberatory Too

Although Universities are often a colonizing technology, they are also complex and can paradoxically be a source of liberation even as such institutions coerce and control. As scholar Michel Foucault has observed, “Where there is power, there is resistance, and yet, or rather consequently, this resistance is never in a position of exteriority in relation to power.” In other words, resistance arises from within power structures and often exists in ongoing relation to such structures.

Historically, many colonial Universities became sites of anti-colonial activism and anti-racist revolution. In South Asia, colleges started by the British government to educate the native populous and prepare them for work within the British Empire became key sites of resistance, particularly during the Indian Independence Movements of the early 1900s. In North America later in the 20th century, the Third World Liberation Front strikes were led by students hoping to change the California State University system. During the Civil Rights era college students were crucial actors in so many campaigns, helping develop and popularize tactics like sit-ins and teach-ins or engaging in voting rights efforts like Freedom Summer. Many Native American leaders involved in the occupation of Alcatraz island in 1969 were also brought together through university experiences, including several student leaders at UC Berkeley. (Ironically, many American revolutionaries also were radicalized through colonial universities prior to declaring independence from Britain way back in the 1700s as well.)

Many of these radical groups were explicit about their beliefs that education is a key tool for liberation (ala Paulo Freire), and prioritized the creation of alternative systems of schooling. So the TWLF contributed to the founding of Ethnic Studies, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) formed Freedom Schools as part of their larger campaign to ensure greater voting rights for people of color, and members of the American Indian Movement formed Survival Schools that contributed to the global movement for indigenous decolonization (Davis 2013).

As much as graduate programs can be a colonizing force, they can also be liberatory spaces. This is particularly true when graduate students get involved in revolutionary forms of activism, including labor organizing. Their experiences struggling within and against dominant structures of power often serve to radicalize students, and their studies provide them with skills they can turn against institutions of power in creative and strategic ways, thereby building strategically coordinated points of resistance. Despite the difficulties of graduate school, or perhaps because of them, I definitely experienced this type of radicalization during my own graduate program. In many ways I feel like I learned more from activist work during school than from formal classes, although both experiences existed simultaneously and in relation to each other.

School in general, and graduate school in particular, is a rite of passage, a ritual tranformation. But it’s not a simple linear transformation–it’s transcorporeal. According to Stacy Alaimo (2018), “Trans-corporeality means that all creatures, as embodied beings, are intermeshed with the dynamic, material world, which crosses through them, transforms them, and is transformed by them.” Graduate school makes everything feel like it shifts. You feel it in your body (e.g., depression), it transforms your worldview, and it changes your relationships to the world around you, including your relationships with your family or your environment, in a multiplicity of ways, some good and some bad. It can be harmful for one’s health. It disrupts you, but that disruption can create space for liberation. Graduate school is never just one thing, just as you are never just one thing. In this sense, the question becomes not how we abolish such power structures entirely, but rather “what forms of power do we want to live with and which forms do we wish to limit or prevent?” (Thorpe 2012) How do we make University spaces work for us, and how do we minimize the negative and harmful aspects of such spaces?

These contradictory elements, the University as a space of oppression and potential liberation, reflect both the risks and the power inherent in graduate degree programs. After my own experiences surviving graduate school, I feel like the challenge is to learn to live within that paradox, recognizing the social injustice at the root of University education systems and using that as motivation to advocate for changes to create more just and equitable communities.

Crafting Support Networks as Resistant Praxis

The colonizing nature of schools seeks to divide us, isolate us, and make us feel like we have no power compared to those above us in the hiearchy. The idea of “prestige” and “professionalism” is often used as a gatekeeping mechanism. But school systems also bring together like-minded people who can provide structural supports for liberatory organizing work in the form of working groups of scholars, student organizations like graduate student associations, and especially unions.

We are always stronger together, and navigating the pitfalls of graduate school is easier if you can find a support network to rely on. Some of us are privileged enough to have existing networks of family or friends, but graduate school also expands our networks exponentially and cultivating relationships with like minded people you meet in your programs can be crucial social capital.

Navigating graduate school without being seduced by the powers that be and losing connection to liberatory politics on the ground also requires having folks who can hold you accountable. Academia encourages us to make our ideas understandable only to a select few, to use big words and fancy terms to sound professional and signal our belonging to an elite group. Losing our ability to connect to regular people and breakdown social issues in ways anyone can understand effectively deters dissent and intersectional organizing work. Having diverse support networks can prevent you from feeling isolated and can make it easier to survive and challenge the various struggles that we face during graduate programs.

What you learn in graduate school only matters so much as it is connected and embedded in the web of relationships with our human peers, other-human kin, and ecosystems. Do not let yourself become isolated. Whatever you learn only matters in the context of the world we are situated within.

Make connections, particularly with other graduate students and especially across disciplines. Don’t be afraid to reach out to faculty at other Universities. Retain and develop connections with folks outside of academic spaces.

Recognize that not all folks want to or can go on to a tenure track faculty job. Grieve and rage as you need to given the difficult job market. Consider the power of possibility–what calls to you? What are you willing to do? What options do you have? For sociology folks especially, we have many routes for employment outside of academia, and all the more power to you if you can recognize that navigating the toxicity and power dynamics of academia might not be for you. Coming to acknowledge what we don’t want to be a part of is just as important as discovering what spaces and networks we do want to be a part of. Think about your ultimate goals (plural) and try and see how you can form connections with people involved in those areas while you are a student. Use graduate school to build the web of relationships that can help you work toward a better, more liberatory, socially just future.

Navigating the Paradoxes of Conferences

Of all the experiences during graduate school, conferences are perhaps the academic activity I am most conflicted about. It took me a long time to attend a professional association meeting, largely because this was an area that I lacked any mentorship on (alas, an all too common problem graduate students tackle, good mentorship is hard to come by). By now, I’ve attending some national ones as well as some smaller local professional meetings. In some ways, I wish I had discovered conferences sooner. In other ways, I never want to attend another conference again. I think my own conflict about conferences stems from the fact that, just like all of academia, professional meetings can be oppressive yet also potentially liberating experiences.

Conferences can be very expensive, making it difficult for students and adjunct faculty to attend, thereby replicating larger systems of inequality across academia. More prestigious universities often provide more funds for tenure track faculty to attend conferences, which also means there are inequities between R-1 and teaching oriented institutions in terms of who can go and who has funds to pay for memberships in professional organizations. Conference attendance can also significantly contribute to climate change, something I wish folks talked about more. Bigger conferences are typically more beuracratic and hierarchical in structure (here’s to you, Weber). They are also more likely to be invested in notions of professionalism, which I personally found very daunting to navigate as a graduate student. However, my experiences at more local and feminist-oriented conferences has generally been more casual, supportive, and positive.

I think as a graduate student, if you are interested in seeking a tenure-track job and have access to funding support for travel costs I would encourage folks to go to conferences, particularly local ones. Sometimes you’ll have more funding for travel as a graduate student than you will as a lecturer, for example, and with the job market being as challenging as it is right now it can be helpful to at least attend while you have access to some institutional support. I went to bigger conferences later on during graduate school as I went on the job market, but I wish I had gone earlier when some had come through my local region, just to get a feel of them as an attendee. They can be overwhelming, anxiety producing spaces. They can also generate many ideas or be good places to network. Costs, though, can be a huge barrier–it’s messed up, but real. Smaller conferences can be less pretentious and more creative spaces, where you can make stronger and more personal ties to academics in your region. They are also less expensive. If you are a student or in a precarious employment situation, many professional organizations also provide travel grants which can be a small help and are worth pursuing if you qualify.

I learned to think of conferences as opportunities to get creative, where I can write or present on projects that are not necessarily part of my dissertation work. Conference calls or other calls for papers often draw on specific theoretical approaches or topical areas, including those you might not typically consider in relation to your own work. Exploring how conference themes or CFPs relate to your interests can help you approach topics in new ways, or give you ideas for new projects. With that said, conference calls can also constrain approaches to topics, too. But in general, they allow you to explore other areas and work on side projects without the constant oversight of your advisors. This gives you more creative freedom to explore what you are interested in as well as how you like to write and research.

Conferences are always a blur, and it’s important to manage your time and energy–you cannot go to everything, nor should you try, so prioritize your time and don’t feel poorly if you need to take a break. Attending sessions at conferences can help you learn about ongoing work or new methods and areas of research you aren’t as familiar with. If you approach the conference with a critical lens, it can also help you learn more about what gaps exist, what work is not being done or at least is not visibly being promoted in professional organizations. For example, when I was at the American Sociological Association meeting in Montreal a few years ago, there was literally ONE session dealing with colonialism. One. And it was run by the Canadian Sociological Association. That is extremely telling about what scholarship ASA prioritizes, or more accurately, deprioritizes.

Conferences can also be an opportunity to collaborate with others, and to form new connections. I like to reach out to academics I know beforehand to see if they will be attending and try and say hi while people are there, even if only briefly. I recommend following up with folks you meet directly after the conference is over, before you forget to. Social media can also allow new connections to continue to develop even if you aren’t geographically close.

In general there are SO many academic associations out there that do regular meetings and conferences, it’s worth doing some digging to get a sense of what ones you are most interested in attending. One resource I wish I had known about sooner is HNet (Humanities and Social Sciences Online), an online network system for academics where folks can access discussion boards but also CFP announcements from various journals and conferences.

Recognize that conferences, as with most academic spaces, are part of the colonial education system. They are often very surreal spaces to be enmeshed in, and have their own politics and drama. Graduate school does not necessarily make you a kinder, more compassionate, more ethical human being. Learning does not necessarily translate into having a strong moral compass. The nature of professions means that those people who most adhere to the colonial values of the system often rise to the top. Working within the system can be important, but is only possible when we maintain a critical, humble, and inquisitive compassion to the web of relationships around us.

Importance of Creative Writing & Reading Spaces

A sad truth of graduate school is that experiences in academia can make you hate writing. Many of the forces of academia are designed to teach you how to engage in a particular type of writing, especially styles that will get approval from organizations or people who are granted legitimacy. Before graduate school I used to write for fun, for emotional release, for creative imagination. It’s easy to lose sight of writing for pleasure, for joy, or for resistance when writing becomes work that has to meet the approval of numerous people on your committees.

I found it very important to develop room for creative writing, like blogging, private journals, poetry, or fiction, which can make writing more than a chore or task. It’s not something I engage in all the time, but writing for yourself allows you to find your own voice. It makes it easier to maintain the clear perception needed for critical self-awareness that allows us to navigate the colonial education system without uncritically reproducing its oppressive nature. To paraphrase Toni Morrison, write what you want to read. Finding a space to share this type of creativity that won’t be high stakes can also be particularly freeing, where the people who are reading your work can’t force you to change it (unlike, for example, writing work done for one’s degree that has to be approved by committee members for you to graduate).

My blog actually started as one of those spaces–I wanted to explore ideas, practice and play with writing without having to worry about oversight. It’s been a rewarding experience. Though one thing to note about social media in particular (e.g., blogs) is that it’s also a weird time-capsule. Although you can of course always go back to things to change old posts, I haven’t. I think it’s good to be reminded of the journey I have gone through and while I don’t necessarily agree with everything I once shared, I think it’s good accountability to keep it all up as a sort of archive of my own transformation throughout my time in academia.

I also think one of the most rewarding things I ever did was pursue what might be called “creative reading” space, particularly with scholarly work. It can be hard just to keep up with the reading material assigned in graduate classes, so adding additional reading on top of this can be difficult. But I found that it was by branching outside of what was assigned in courses that I really found out what I was interested in and what areas of work I wanted to contribute to. I also realized there was so much more amazing and radical scholarship out there than I had previously been exposed to, and I felt more empowered to do that type of work and felt less isolated during that pursuit. Don’t get me wrong, I also was exposed to amazing scholarship through my classes, too, but there’s something different about discovering new areas of research for yourself.

Things like academic article searches for fun on topics that interest you help you find out what type of scholarship exists, mapping scholarly communities. Google the scholars you like, or scholars you don’t know about–who are they? What’s their background and politic? Do they have any filmed talks? Use “related readings” algorithms on sites to your advantage to find new work. Skim things. Read abstracts. Save readings you are interested in (within intensive folder systems if you are like me, and remember, back that stuff up!).

One of the best things I ever did was sign up for table of content alerts for journals I was interested in. You can usually do this easily with at least some journals through the library system, where you sign up for alerts when a new issue comes out. You will likely discover interesting articles that help you think about your research, yourself, and our world. We have rare access to a lot of information as students or academic workers that is typically kept behind outrageous pay walls. Don’t miss that opportunity. I also love sharing things with folks I know when I see something I think they would like.

Reading for fun allows you to learn more about methods and teaching pedagogy. This likely only applies to folks who really want to stay in academia beyond graduate school, but I don’t think I was alone in feeling frustrated by inadequate training in methods in graduate school. Continuing to read scholarship directly about methods or teaching pedagogies can inform your own research and change the way you design your classroom spaces. For example, I was recently at a conference where a session organizer had never heard of photovoice methods before. This was a tenure track faculty member who had never even heard of participatory action research methods. And to be honest… at that session I was reminded I hadn’t heard about it in graduate school either. I found out about photovoice and PAR through my own digging into feminist theory. I haven’t used any of these methods yet in my own research, but if I had known about them sooner, I might have been able to and I hope to someday create a project that does.

Remember… It’s Meaning/Less

In closing, the final reflection and take away I have from my time in graduate school is the hope that as an Assistant Professor, I remember that obtaining my Ph.D. is ultimately meaningless. Allow me to explain.

In some ways having the degree is a huge, meaningful, and important milestone and accomplishment that is worth celebrating. It is a rite of passage. But despite the degree having so much meaning, after everything I have been through and seen and learned about academia, I truly believe that my degree is also completely meaningless. So many amazing scholars are pushed out of academia. We are constantly losing folks. This is often due to circumstances beyond our control, in ways that are unpredictable and tied to privilege and power relationships. All it takes is one medical emergency, one breakdown, one year of lost funding, one abusive advisor, or the list goes on, to completely derail a talented and amazing individual from finishing their degree. Yes, I finished. But that 50% drop out rate means that my finishing is basically a coin tossed in a bucket. I got lucky. I had privilege.

So where does that leave me? Where does all this leave all of us in academia? Graduate school teaches you a little about a lot of things, and a lot about very few things. If I have learned anything, it’s that I know nothing. Most of the knowledge produced in academia is not from academics–it’s from the people we study, the organizations we do ethnographies on, the data we analyze. And that all exists out there in the regular world. Just because academia legitimates particular forms of knowledge, doesn’t mean that it’s the only source of truth or wisdom. A lot of academic work has historically been rooted in projects of Empire, and a lot of academic work still is.

I think it’s vital to stay humble. I look forward to continuing to learn and grow as I enter into my role as a tenure track faculty, but always a student.