Coauthored by: Amara Miller and Joanna Johnson

The latest scandal in the US yoga world: it turns out well-known yoga teacher and teacher trainer, Eric Shaw, is actually a deep-seated, unapologetic misogynist and sexist. This revelation is turning heads among practitioners and teachers, especially in the post-Trump moment where we have a growing culture of cruelty, a slew of domestic abusers in our highest offices, a crack-down on women’s rights, and rising right-wing nationalism and white supremacy not just in the USA but globally. Although Shaw is US-based, the escalation of neo-fascism is worldwide; the issues raised here will therefore have their own particular country-specific manifestations, relevant to the worldwide yoga community.

Today we will be writing about misogyny, sexism, and patriarchy in yoga, and the ways we are all complicit in these systems.

The Hateful Rant (aka Misogynist Tears!)

On Thursday, February 16th, Eric Shaw posted a note to facebook titled “Masculinism 101: A Response to the Feminist Recoding of History” (to read his original post, go here, but be aware: trigger warning). Yoga Dork has already covered the incident, noting they “believe that you should know if your yoga teacher is a raving misogynist.” We completely and wholeheartedly agree.

We’re not going to rehash all the hateful, spiteful, and untrue things he has to say about women, women’s history and accomplishments, and women’s oppression. This blog is not about a point by point rebuttal, because all his points have been well-researched and debunked by feminist scholars over the decades. With that said, we do think it’s helpful to get the gist of his rhetoric.

Shaw begins his epic rant with the words “How about this vision? Women have been cowards.” He goes on to claim they “sucked the wealth and life-blood out of men to enjoy their baby-making efforts while men went out and did the real work in the world.” He asks: “We’re to trust that the gender that has been passive, supplicant—arguably ‘parasitical,’ to quote Simone de Beauvoir—is overnight competent, self-possessed and unyielding enough in composure to handle the pressures of public responsibilities?” (Feel like projectile vomiting yet? And also, way to adhere to a gender essentialist argument and a lack of recognition of gender fluidity, Shaw.) Apparently, Shaw contends, “we could just as easily demonize women for being a kind of succubus. For dodging their social responsibility and hiding behind a veil of too-moral dignity to dirty their hands with the affairs of the world. We could say women were cowards for hiding in the home and not successfully challenging men to take up their fair share of public responsibilities.” (Whoa there. Way to victim blame those oppressed for the acts of oppressors subjugating them?)

Shaw’s post oversimplifies and completely misinterprets history in pretty much every way possible, focusing on the vantage point of those who have historically (at least!) been oppressors and abusers with absolutely no nuance (which is super ironic considering his one and only academic working paper on abuse during BKS Iyengar’s childhood). His post makes it clear that he doesn’t know a thing about women’s historical accomplishments or the way patriarchal systems often erase such feats, symbolically annihilating herstory and taking sole credit for accomplishments only made possible because of the work of women. Eric is clearly another brick in the wall of our education system, who ate up patriarchy in our schools and now regurgitates it at will.

According to Eric’s position, there are no people of color anywhere in (cue dramatic music:) all of time. This means every time he says “women” or “men”, he is only referring to white folks and their experiences. So to be clear, not only is this rant an epic, extreme example of misogyny, patriarchy, and sexism at work but it is also deeply embedded in white supremacist culture and educational experiences that whitewash and enforce a Eurocentric focus in historical retellings. We can add to the list of Eric’s flawed thinking: it is racist, because this type of language and hate speech is also directly supporting racism, “a system of advantage based on race” (Wellman 1977).

According to his Facebook info, as an undergraduate Shaw attended Willamette University from 1979-1981 where he studied Art, Biology, and “Intellectual History” (note: this isn’t actually a major?). Later on, he studied yet more Art in Santa Cruz (art has historically been an incredibly white, patriarchal, and misogynistic system, so no surprises there). He then got an MA in Religious Studies from the United Theological Seminary in 1995 (including studies in “Church History”), an MA in Special Education in 2000 (ye gods, really? with those misogynist views?), and finally an MA in Yoga History and Philosophy at the CA Institute of Integral Studies in 2011. His bio shows he began teaching yoga in 2006 at UCSF Medical Center (we can assume to patients), and has taught at several renowned studios including YogaWorks from 2009-2010, Yoga Tree from 2011-2015, and most recently at the Dallas Yoga Center (although apparently he was fired after his diatribe–good on them!).

In other words, Eric Shaw has never actually studied history in an academic setting outside religious or spiritual contexts. More telling, as far as his biographical information out there indicates he has also never taken a single course in feminist theory, women’s studies, or gender studies (and from his tirade, it’s clear he hasn’t read such scholars/activists on his own either, or if he has he clearly hasn’t understood them). Despite his lack of study in these areas, in typical entitled, white, male fashion Eric Shaw believes that he should be able to mansplain women’s history and feminism to women and long-time, actual feminists who have been studying, researching, and living this work for decades. Because: patriarchy. And white supremacy.

The irony is that his whole argument is pretty much “patriarchy sucks for men, too,” which is an argument that has already been made by feminists for literally decades, and what’s even more ironic is that feminist work on this very topic is much more nuanced, accurate, and articulate (aka, way better than Shaw is capable of, despite his claims of male superiority). He incorrectly puts the blame for men’s pain on those victimized by patriarchy (women and feminists) rather than understanding that it is patriarchy that ultimately causes the suffering of the men he is so concerned about, not feminism. Frankly, Shaw’s entire take on feminism, gender relations, and history is so completely off track that, as Yoga Dork notes, it “reads very Onion-y” and at first seemed satirical to commenters, many of who “couldn’t believe” a yogi and well-known teacher could harbor such hateful, spiteful, and dangerous views.

And, let’s be real here, these types of views are dangerous. This isn’t some “opinion” to be debated. As long-time activist Teo Drake said in one of his comments, “What Eric Shaw put out into the world wasn’t an opinion to be disagreed with. It was violent rhetoric. There’s a big difference between being imperfect (as each of us is) and crossing over into abuse.” So we need to understand Shaw’s post is an example of violent rhetoric designed to dehumanize, demean, and target an entire class of people with violence, harassment, and assault, and which then attempts to legitimize such harm by claiming victims “deserved” to be abused (completely creepy, and complete BS).

Misogyny is a undeniable motivator for men committing violent crime (fact: men are the perpetrators of most violent crime). For example, according to research on intimate partner violence in the USA, men “with a history of committing domestic violence are five times more likely to subsequently murder an intimate partner” (Aalai 2016). Research also reveals “nearly 60% of all mass shootings (defined by the killing of four or more victims) have roots in domestic violence” (Fairweather 2017). And it doesn’t stop there. “‘When you are trying to predict violent recidivism, you tend to find that domestic violence is one of the strongest predictors,’ said Zachary Hamilton, who studies risk assessment as director of the Washington State Institute for Criminal Justice. He cited an analysis of criminal offenders in Washington State, which found that a felony domestic violence conviction was the single greatest predictor of future violent crime” (Jeltsen 2016). In other words, misogyny is often the canary in the coalmine for other forms of violence, and one of the root ideologies violent offenders adhere to.

This type of misogynist rhetoric is also one of the ways online communities of Neo-Nazis and the “alt-right” prey on and recruit men to their cause (how’s that going for you, Shaw?). In the article “How the alt-right’s sexism lures men into white supremacy” Romano notes that “the gateway drug that led [members] to join the alt-right in the first place wasn’t racist rhetoric but rather sexism: extreme misogyny evolving from male bonding gone haywire.” All of this is why white nationalist organizations, which are predicated not just on an adherence to white supremacy but also deeply held misogyny, queerphobia/transphobia, anti-Semitism, anti-immigrant sentiment, and Islamophobia, are growing much faster than other terrorist organizations and are considered more dangerous than other terrorist groups in the USA today.

There is a reason the most recent rise of “alt-right” white supremacist groups has been linked, not to racial politics, but to Gamergate, the misogynist attack on feminists critiquing the video gaming industry that occurred in 2014. As Lees notes, “The similarities between Gamergate and the far-right online movement, the ‘alt-right’, are huge, startling and in no way a coincidence… Its most notable achievement was harassing a large number of progressive figures–mostly women–to the point where they felt unsafe or considered leaving the industry… this hate was powerfully amplified… leading to death threats, rape threats, and the public leaking of personal information.” This article fails to mention misogynists also engaged in bomb threats as well as rape threats against these women’s children, leading some to develop PTSD symptoms or to retire for their and their family’s safety and well-being. (So, if people would like to ignore the realities of violent misogyny and continue to bury their heads in the sand, go ahead and continue practicing avidya, ignorance, and keep up with the arguments that Shaw’s views are somehow “a valid opinion.”)

Misogyny kills. Misogyny maims. Misogyny traumatizes, harrasses, and assaults. And Eric Shaw, raging and unapologetic misogynist that he is, is deeply complicit in this system of oppression and violence.

But it must be a mental breakdown–not so fast!

Those appalled by the hate apparent in Eric Shaw’s post, the blatant misogyny, sexism, and lack of respect for women generally, have been quick to claim that he must be having some sort of mental breakdown–that he must be mentally ill, or that he must be going through some deep inner turmoil. That he is really a “good person” who is just not well. Take, for example, comments like these: “what he has written sounds like a mental health crisis,” “Eric, are you ok?”, “this must be a sick joke, or he has had some psychotic break.” In the days following the initial post, every Facebook thread that we read included some well-meaning, but sadly politically ignorant yoga practitioner exhorting us to “have compassion” for Shaw (never mind that the assumption a practice of yoga equates to compassion, that “yoga = compassion,” is a recent and perhaps even false conflation of what yoga is, rooted in capitalist and new age appropriations of the practice).

The claim that those who engage in hateful speech and violent behavior toward others only do so because they are unwell is based on a Christian understanding of a good-evil dichotomy, where people are considered either “good people” or “bad people”. This type of thinking has infiltrated yoga as the practice moved to the West, so it’s no surprise that many people reading Eric’s post are struck by the paradox and dichotomy–is he a “good person,” as some people have personally known him to be, or is he “bad?” And if he is “good,” then it is assumed he must be mentally ill, have had a psychotic breakdown, or be otherwise “out of his mind” to also, simultaneously, be a raging, dangerous misogynist. But real life just doesn’t work this way.

Sociologists and psychologists have long researched the way seemingly ordinary, “good people” can engage in horrific acts of violence and oppression. The term “banality of evil” is not referring just to the way evil is part of our everyday lives (in other words, that evil is banal). It also refers to the fact that most people who engage in evil acts are in fact ordinary, boring, “good people.” (See, for example, Milgram’s shock experiments or Zimbardo’s The Lucifer Effect.) So we need to be clear that someone can be a “good person” in certain areas of their life and still do atrocious acts (and can do so even with the best of intentions). Eric Shaw could indeed be a “good man and a good friend” to some people as some did claim in their comments and still who hold dangerous and harmful views about women that manifest in harmful ways towards others. One does not preclude the other, and ultimately, Shaw needs to be accountable for all his actions, especially those that are damaging, and perhaps most particularly when bigotry is conflated with yoga.

The problem with the argument that misogynists are just mentally ill is that it serves to medicalize abusive behavior, rather than recognizing that perpetrators are often perfectly “sane” by any psychological measure and yet still hold abhorrent views. As Baxter (2017) notes, “Every time we willingly blur the line between raging arsehole and mentally ill person, we do two very dangerous things: we increase stigma surrounding real psychiatric conditions, and we excuse people for their terrible behaviour on the basis that they had to have been ‘out of their minds’ to think or act that way… It’s also easy to see how we then stop holding people account for abuse, for cruelty, for prejudice and xenophobia.”

Rather than further stigmatizing mental illness, we need to recognize that seemingly “good people” can in other areas of their lives do great evil. We need to be able to call this type of behavior what it is, without medicalizing it: systematic oppression, abuse, and a profound disrespect. Sure, Eric Shaw could probably use some serious psycho-analysis and therapy from a licensed professional, although he’s not likely to seek that out given he seems to believe he is completely in the right. But as of right now, all comments, conversations, and posts indicate that he is indeed perfectly sane, if completely despicable.

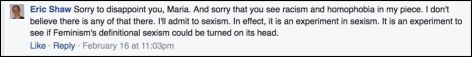

In other words, let’s call a spade a spade. Eric Shaw is not mentally ill. He has repeatedly claimed he “is okay,” despite the completely ridiculous concerns of commenters. He doesn’t want help and he doesn’t believe he needs it. He has openly admitted to being sexist, and has essentially said he’s cool with that. He is utterly unapologetic about his diatribe of disgusting hate, claiming in typical entitled white male fashion that he feels “disrespected” by the justifiably angry responses he has received. He has repeatedly, again, and again claimed he stands by everything he said, no matter how incorrect, no matter how damaging/harmful, and no matter how simplistic. This is not someone open to dialogue. This is not someone open to learning. This is not someone willing to engage in healing or willing to admit they were wrong.

His hateful, misogynist views do not make him mentally ill, they make him dangerous. These views make him complicit in the continued oppression of women everywhere. These views make him potentially abusive to his own clients, friends, and family. And these views make him disrespectful, completely uncaring, and disturbingly unconcerned about the harm his words have and do cause others.

It’s also disturbing that there seems to be a great deal of commenters focused on emotional concern for Eric Shaw, his feelings, and his health, rather than concern for those traumatized and targeted by his hate and spite. Many commenters have sent “love and healing” toward him. Others have reached out to make sure he “is okay.” The incessant worrying from commenters about his well-being refocuses attention and care back on someone who is propagating, supporting, and spreading abuse and oppression. In other words, it serves to refocus attention and emotional care work back on the abuser, rather than focusing on supporting those victimized and harmed by this type of abusive language. In this way, despite undoubted good intentions, everyone whose main concern is for Eric is actually upholding the systems of oppression that obscure the lives of victims and reward the deeds of abusers.

Attempting to tone police those most affected and harmed by this type of violent rhetoric while also refocusing attention back toward our abusers does nothing to combat hate, and inevitably actually supports, condones, and excuses the abusive behavior. Tone policing is a silencing tactic, and is one of the ways systems of oppression are reproduced and protected. It’s also a classic symptom of victim blaming, which argues that the justified anger victims feel toward those who abuse them is in fact the reason why they are being abused. In reality, abuse is a conscious choice made by the abuser. Resistance to oppression is not the same as oppression, and one never has to be kind to their abuser. We should never ask people to express love for their abuser in order to have their concerns heard. Ultimately, by engaging in tone policing and victim-blaming, society allows abusers to perpetrate violence while avoiding accountability for their actions. People have a right to be angry about this type of dangerous, hateful speech. This type of misogyny is what leads to policies that target women’s rights. It is what leads to violence against women that is a deep and powerful part of patriarchal systems of oppression designed to keep women “in their place.”

The way to stop abuse is not to say “stop” more nicely. It’s to say “no more!” as fiercely as necessary. The way we stop oppression is by supporting those who are victims of abuse (rather than supporting the abuser as if they are the one being harmed and the one we should be immediately concerned about). It’s ensuring those engaging in abuse will be held accountable for their actions and choices. And yes, this might include informing their employers so they can take appropriate action to reprimand or distance themselves from a dangerous person. It might include boycotting any of the products, services, or trainings a dangerous person sells. Hell, sometimes, it might even entail protesting against an organization that is colluding in covering up inappropriate behavior.

Then it’s an isolated incident–not so fast!

While it’s tempting to argue that Eric Shaw is just a “bad apple” in a sea of otherwise wonderful yoga people, the reality is much more complex. Commenters on his post have actually indicated Eric Shaw’s rant was not some isolated, out-of-the-blue incident.

Two yogis recounted how: “I was treated to a live version in my kitchen one time, much to my great discomfort. I remember us having to agree to disagree. It was a charged discussion and I felt little leeway in the ferocity of your opinions. The tone of your original post is so hateful toward women and being a woman I am, frankly, revolted [by] the perspective you claim to be ‘investigating,’ but which actually seems pretty entrenched.” Many indicated they had misgivings about him, feeling strongly that something was “off” or that he “gave [them] the creeps.” One commenter noted how “He did one workshop at my studio on ‘women in yoga.’ The students afterwards told me it was the worst workshop they have ever attended and that he wasn’t very bright and the content was low level… I’ve always felt he was a creep but like all of us, we want to give people the benefit of the doubt.” Another individual recalled how “[Eric] taught yoga philosophy in my yoga teacher training five years ago. You shared your misogynist opinions with a group of mostly women and we were quick to speak out against you. I’ve seen a young woman walk out on your class because you wouldn’t allow her to move freely.” Yet another recounted Shaw’s comments on the size of a student’s breasts (too small for him to consider dating her, apparently).

One individual reported how they “sat through several of [Eric’s] workshops over the years trying to honor your scholarship while simultaneously recognizing microagressions against me personally and all other strong woman in the audience who dared question you.” Still others noted, “He taught at my yoga teacher training and was late both days… I also got a weird vibe from him and I’m pretty sure he was kicked out of Yoga Tree Berkeley (rumors).” Another commenter recalls how, “I met Eric Shaw at the Anusara grand gathering years ago. He seemed like he idolized John Friend. In hindsight, this seems all very telling. Something didn’t feel right then either.” Another indicated that “Eric Shaw, who advertises himself as a yoga teacher, has made racist comments on Facebook before.” One yoga instructor, who once had Shaw as their student, recounted: “Frankly you were one of the most self absorbed yoga students I ever had (I’ve known Eric for well over a decade)… Reports I have had from people I trust also peg you as quite the misogynist, and womanizer (yes I know you’ve been pretty fucking slimy with people I know).”

Eric Shaw’s disturbing and dangerous views went relatively unnoticed in the yoga world for a long time, even though he was teaching primarily women. This is despite the fact others had raised concerns about him in the past, and that he publically wrote a very similar hateful rant in 2013 that was published by Elephant Journal titled “Feminism Sucks.” In other words, his most recent invective was a long-time coming, a long-time felt, and frankly, a long-time known. But, his career wasn’t ruined in 2013 when this type of violent rhetoric was first published. Concerns simply didn’t gain traction and visibility in yoga, where it was all pretty much tolerated and buried–until now, in the broader context of the post-Trump, post-Brexit moment when this type of hate makes women, whose rights are already under unprecedented attacks, that much more fed up (and that much more capable of sharing their anger and disgust through social media).

Because Eric seemed like such a “good person” in other areas of his life, people found it profoundly hard to believe that he was also very much a hateful misogynist. It is also likely that the brushing off of any concerns was in part because those who were concerned were primarily women, and as we know in patriarchal systems the concerns of women are often downplayed, ignored, or excused as “overreactions” or “hysteria”. (Which, by the way, feminists have studied the deeply disturbing history of as a catch-all psychological diagnosis called “female hysteria”, often used to target and punish women acting “out of line” in the 19th and 20th centuries.)

Eric Shaw’s post is an obvious and blatant example of misogyny at work, making it easy to recognize and almost comical in its hate, disconnection, and ignorance. But the reality is that misogyny is often far more subtle, harder to recognize, harder to combat, and harder to uproot. The impacts of patriarchy live and breathe in our culture, in our yoga communities, and in ourselves in ways that are often extremely difficult to recognize, let alone resist. In other words, Eric Shaw is not just a “bad apple” in an otherwise pristine, perfect, and “conscious” or “woke” yoga community. The type of misogyny that Eric Shaw spouts is the extreme manifestation of underlying, persistent issues with patriarchy and sexism in the world at large – and within yoga. “The truth is that there is no such thing as a lone misogynist – they are created by our culture, and by communities that tell them their hatred is both commonplace and justified” (Valenti 2014). Eric Shaw’s post is, in this sense, the canary in the coal mine.

Misogyny–especially the more common subtle forms of misogyny, patriarchy, and sexism–functions in part through our own complicity in tolerating, excusing, and condoning such attitudes and behavior. We must not excuse Eric Shaw as one bad apple in a world of seemingly good ones. Misogyny affects and infects all of us and the spaces we move and act within, and it takes active, deliberate, and continual work to uproot. It takes a profoundly deep and committed practice of yoga to engage in the type of uncovering and Truth-seeking required of us to uproot these biases, to recognize the subtle ways our practice is infected with oppression as well as the way we ourselves are complicit in such systems (especially those of us who are privileged enough to actively benefit from such systems). This is work it seems Shaw is unwilling or unable to do.

The easier, more comfortable, and more common thing to do in response to Eric Shaw’s post is to claim that it is simply an isolated incident, that it “doesn’t happen in my circles,” or that it’s not something prominent in the yoga world at large. But doing so would be a mistake. We want to believe that yogis and yoga communities are better than this type of hateful and violent rhetoric, that yoga somehow magically roots out this ignorance and hate, that if we just practice “all is coming.” But this is a romantic expectation that denies the realities of the way deeper practices of yoga have been compromised by settler-colonial appropriation of the practice and have always been deeply rooted in patriarchal systems. This type of approach only serves to trivialize misogyny as the isolated purview of seemingly disturbed individuals, rather than allowing us to understand this type of incident as a symptom of a larger issue in the practice of yoga and in our culture at large. It fails to place this incident in the context of patriarchy, “a system of social structures in which men dominate, oppress, and exploit women” and LGBTQ+ individuals, in ways that harm all sexes and genders (Walby 1990). Misogyny and patriarchy are deeply embedded in most social settings, and to deny the possibility it is part of all our yoga communities, and even a part of ourselves, is ignorant and naive. The question is not “what if?”, it is “in what form?”

Take, for example, this story from one commenter on Eric Shaw’s post:

“Through my close involvement with a spiritually based supportive group some years back, I came to see that misogyny was alive, well, and kicking, albeit in an underground, deeply unconscious way. A known predator (male) was preying on vulnerable young women as they joined the group; countless women had complained about this, but the men banded together, denied any wrongdoing, trivialised the women’s concerns, accused them/us of hysteria. I was baffled, many of these kind, intelligent men were friends of mine [for] several years; I couldn’t understand what was happening. Anyway, long story short, I gradually realised that these ‘new men’ were still carrying the wounds and warped messages from their forefathers, their families of origin, and from society, but that intellectually, they’d seen and accepted that sexism existed and that women suffered greatly–but their deeply felt anger, rage, etc. had just gone underground, only to emerge by leaking out into everyday interactions as described above.”

Although it didn’t get the audience it warranted when published, we can look more closely at Eric Shaw’s 2013 piece titled “Feminism Sucks” to investigate the way institutions often excuse and enable misogyny. This was work that was given a platform by Elephant Journal, known for publishing other controversial clickbait like the recent article by a so-called “yogi” titled “Why I Voted for Trump.” With the increased traffic to Shaw’s 2013 article in the last few days, Elephant Journal has since deleted the offensive piece (which, thanks to internet archives will never be completely gone).

While at a basic level we commend EJ for removing the piece, let’s delve deeper into how and why they did so. Was it because they finally realized “this is a really hateful and violent thing to provide a platform for, and we don’t want to support that so let’s delete it?” Unfortunately, this is not the case. It was because they were likely getting so many complaints from women triggered by and concerned about them providing a platform for this type of hate and the inappropriateness of the article. They were forced to take it down before they were dragged into the scandal surrounding Eric Shaw (four years too late, EJ!). In other words, it was a business decision, not a moral decision. The moral decision would have been to never publish such a piece in the first place. They also haven’t openly admitted why the article was problematic, or why they deleted it, or even taken an explicit stance against the views Shaw expressed in that article which was available on their site for four years (nor did they do so originally in an editor’s note at the beginning of the article, as they did for the Trump piece linked to above).

So even EJ removing the post was a decision that is flawed–{*poof*} it’s just gone! (Get back to the “edgy” articles about neo-tantra, readers!) But Shaw’s other writings? They are all still supported on EJ’s site along with an author page touting Shaw’s credentials (but lacking any disclosure informing primarily female students and readers to the fact that Shaw is also a raging misogynist). So now when people look Shaw up online at EJ they will not actually be able to see what his detestable and dangerous views are. In essence, EJ has completely erased any evidence of Shaw’s hate while continuing to support him as a contributing author, serving to further enable him. Oh, the subtle and insidious ways misogyny works!

Or take the American wing of the Yoga Alliance, for instance, who had this post brought to their attention and were asked to forward their formal statement to Shaw so that it could be more widely shared amongst the worldwide yoga community (note: this is not the same as actively unearthing ethical infraction; because of their lack of regulatory ability the onus is on YA members to inform upon each other). Their response:

“All grievances are private to Yoga Alliance. We do not share that information. Yoga Alliance supports having the public make informed choices when selecting a yoga instructor or a yoga teacher training program, including based on whether a teacher’s or school’s philosophy is aligned with the that of the student. Yoga Alliance Registry’s social credentialing system is designed to allow the public to see feedback from past trainees before enrolling in a training program. Yoga Alliance also encourages prospective yoga students to review other available information when selecting a yoga teacher.”

In other words, despite their belief that they are supporting “having the public make informed choices,” Yoga Alliance is doing nothing to actually inform the public and potential students (most of whom will likely be female) about Shaw’s potentially dangerous views, serving to further enable him and condone his behavior. Does your brain hurt yet?

We can see more subtle forms of misogyny and systems of patriarchy at work in the way people have tried to excuse Shaw’s behavior as some sort of mental breakdown or illness. We can see it in the way yogis, including women, empathized more with the perpetrator of hateful discourse than with those affected by it (even if it was harming themselves; but then again, that’s not such a surprise since patriarchy teaches women to put others and especially men first, to love thy oppressor, and to forgive instead of oppose). We can see misogyny and systems of patriarchy at work when we look at the way yogis, after confirming that “yes he was perfectly fine yet also totally cool with being a sexist pig,” still refused to cut ties with him and decided to remain his friend despite his hateful views, in essence tolerating his actions. These people likely have the privilege to ignore any potential harm done because it doesn’t/won’t affect them directly.

See the full public post from Ekabhumi Charles Ellik here.

See the full public post from Ekabhumi Charles Ellik here.

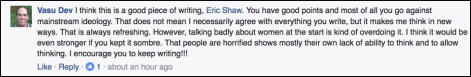

Let’s also not forget that while the majority of people on Shaw’s post were rightfully, justifiably disgusted with the drivel he wrote, there were also others who agreed with him and who were amenable to his ideas. In other words, Eric Shaw is not alone. This was not just other men (though it largely was). It was also (white) women, which isn’t really a surprise when we consider that feminist theory has long indicated women internalize and often participate in their own oppression, especially if they themselves may benefit from white supremacist capitalist patriarchy. Shaw might be an extreme version, but there are many others out there who support his view, who are part of yoga communities, and who also perpetuate systems of oppression.

But, surely Shaw’s yoga career is over–not so fast!

Despite optimistic statements arguing Shaw’s post was “career suicide”, it’s best we be realistic about the ways patriarchy works to hide, bury, erase, condone, and tolerate those perpetrating misogynist hate and violence. Even in the yoga community–indeed, especially in the yoga community–we can see this type of process at work over and over again, where scandals involving teachers engaging in abuse often do not result in their expulsion from yoga spaces or teaching roles. Is this completely messed up? Totally. But does it happen anyway? Yes, all the time.

Historically, there have been numerous “gurus” who have abused students, taken advantage of students, or been otherwise engaged in scandalous activities who have continued to have careers in the yoga world.

Take, for example, Pierre Bernard (originally Perry Arnold Baker) in the early 1900s, who was involved in numerous sex scandals after he created a group called the Tantrik Order. It was alleged that Bernard required participants to engage in “sacramental sexual intercourse” in order to join. In 1909, two teenage girls alleged he had sexually taken advantage of them and charged him with kidnapping, which led to his serving time in jail. But was this the end of his career? No. “Bernard eventually regrouped and founded successful yoga schools in New York City and Nyack, N.Y., where he entertained lavishly, raised a herd of elephants, and taught yoga to the cream of high society” (Love 2012). Not only that, but ““at the time of his death in 1955 Pierre Bernard was a bank president, an officer in Nyack on the local Chamber of Commerce, the head of a large real estate holding company and a member of more than twenty societies, including the British and American Philological Societies, the Royal Society of Arts and the Royal Asiatic Society” (Yoga Dork 2010).

Other prominent “gurus” who have been embroiled in scandals and yet still have gone on to have successful careers include Bhagwan Shree Rajnees, more commonly known as Osho. Rajnees was implicated in a number of serious crimes in addition to sex scandals, including a bioterror attack, an assassination plot to murder a US Attorney, tax evasion, immigration fraud, prostitution, drug-running, drug use, and exploitation of workers. When he was deported, twenty-one countries denied him entry. He ultimately returned to India and his Pune ashram (now one of India’s main tourist attractions) and is still a celebrated figure in many New Age circles today. In fact, his prestige only grew after his death in 1990.

Or take Swami Satchidananda, who rose to prominence after opening the Woodstock Music Festival in the 1960s and was the founder of Integral Yoga institutes across the country. Over the years at least nine women have accused him of sexual abuse, although this didn’t halt “invitations for over fifty years from around the world to speak about the way to peace.” Oh the irony! (You can see his organization’s glowing biography which includes absolutely no record of any charges against him here.)

John Friend, the founder of Anusara yoga, went through what has since been dubbed “Anusaragate” in 2012 when he faced claims of financial mismanagement and a prominent sex scandal, explicit photos and all. Although he reportedly was “left estranged from much of the yoga world, banished from the empire he’d created,” was his career over? No. After a mere year off, he began teaching at a studio in Denver (where “he was welcomed”) and ended up creating/appropriating/adding the Friend branding “magic” to a new style of yoga with (female) teacher Desi Springer, called Sridaiva or Global Bowstring. A mere five years ago, yoga practitioners were optimistically calling Friend out on his numerous ethical infractions and announcing his career was in tatters. Apparently we have short memories, as “his” new style is enthusiastically investigated by both new and long-term yoga practitioners, and the intricacies of the style’s biomechanics dissected in online forums.

Or take the recent Jivamukti scandal, which entailed “allegations of sexual assault and battery against yoga teacher ‘Lady’ Ruth Lauer-Manenti, brought by Holly Faurot, her student at Jivamukti Yoga School in New York City. The suit names Jivamukti founders Sharon Gannon and David Life, as well as studio director Carlos Menjivar, as co-defendants for covering up and condoning Lauer-Manenti’s alleged actions.” (Remski 2016a). Was that the end of any of these people’s careers? No. “Ruth Lauer-Manenti has exited stage right for teaching gigs in Berlin and Switzerland. Sharon Gannon and David Life have exited stage left for retreats in Costa Rica, upstate New York, and then Moscow in the fall” (Remski 2016b). Others commenting on the Jivamukti scandal, such as prominent teacher Leslie Kaminoff (who is well-known for his conservative outlook) “instantly contributed to victim-blaming culture, which enables abuse, and silences those who would speak up.” Despite this, Kaminoff continues to attract large (predominantly female) audiences. The entire incident clearly indicates the ways the yoga world and patriarchal systems in general often work to bury, silence, or excuse harmful actions or violent rhetoric, a process explored by Remski in his last post on the Jivamukti scandal, titled “Silence and Silencing at Jivamukti Yoga and Beyond.”

Look, we believe in second chances. In some of these cases, like Friend’s, there was consent in illicit affairs (if not honesty or truthfulness), so it’s important to note that not all of these scandals involved cases of abuse, harassment, or assault. But the fact is these individuals (mostly men), who made conscious choices embroiling them in disturbing and at times abusive scandals, did not experience “career suicide.” This is a sign that those engaging in abusive and harmful behavior are quite often propped up by patriarchal systems, even, or perhaps especially, in yoga, as their discretions and abuse are consistently downplayed, buried, tolerated, and excused by those surrounding them. Indeed, if we want further evidence of this trend in our broader world we need look no further than the White House, which is now host to a man who was elected President of the USA despite being caught on tape bragging about sexually assaulting women, or his close ties with child sex trafficking networks, or being accused of sexual harassment and assault by over twenty women (including charges that he raped a 13-year old, which were dropped after the victim received a slew of death threats from Trump supporters).

So we need to stop saying Eric Shaw will somehow face “career suicide” after revealing his long-time, deeply-held beliefs of sexism and misogyny, gender essentialism, and indications of racism to boot. Though we wish it were the case, unfortunately, it’s simply not a given. Do we hope Shaw will get the help he needs to overcome his clear biases and to change? Of course. But given the many years Shaw has been engaged in this type of rhetoric, that is not likely to happen, and all the coddling, excusing, and “dialogue” in the world likely won’t do anything to change his mind, no matter how “nicely” we reach out to him. This is a person who has been eating up men’s rights dogma for decades, even while he has never actually reached out to study feminism itself (and that’s one severely lopsided “dialogue” if ever we saw one).

Be Scofield, who is ironically the founder of Decolonizing Yoga, would “love to stay in dialogue” with Eric Shaw regarding men’s rights dogma? The comment does reveal more about how long Shaw has held such views, and how lopsided his study has been.

Be Scofield, who is ironically the founder of Decolonizing Yoga, would “love to stay in dialogue” with Eric Shaw regarding men’s rights dogma? The comment does reveal more about how long Shaw has held such views, and how lopsided his study has been.

Ultimately, to ensure that his career in yoga is actually ended those of us (who are justifiably disturbed by the potential for Shaw to continue teaching predominantly female audiences) will need to stand against him, repeatedly, often, and loudly. It will take denouncing him in our communities and informing others who are considering hiring him in the future about his hateful views. It will take all of us continuing to educate ourselves and our communities on the dangers of such violent rhetoric, the realities of women’s history, and on what feminism actually means and entails.

Where do we go from here?

Happily, most of the comments on Shaw’s post were from people, especially women, who found this type of violent rhetoric unacceptable and disturbing. Here’s a shout-out to all you empowered, amazing people who stood up to combat and denounce hate–you are inspiring. But we would like to encourage all of us to think critically about how we may be condoning, protecting, and potentially even encouraging this type of misogyny in our communities, and how this links to how we teach the practice of yoga.

Thaumatrope: the bird in the cage

How do we break out of the cage of patriarchy, so people of all sexes and genders are able to fully heal? What are we really teaching when we teach yoga, and is there a way to teach yoga as a radical act of social justice? Can we teach yoga in ways that is informed by and rooted in intersectional feminism? What would that look like? How can we promote a spiritually engaged activism in our yoga communities to better combat this type of hate and violence?

Many people are deeply resistant to notions that yoga might be a force for social change or that yoga is political. Even in these Trump/Brexit times, we are often still enmeshed in ideals of yoga that posit the practices as timeless, transcendent, pristine objects rather than the cultural artefacts and tools that they are. This is not to deny the potential power of yoga to support, empower and perhaps even transform a life. But how it transforms us, what it transforms us into and what kind of communities we create as part of that process is up for debate.

We all have an abiding need for be seen and held; to feel part of something greater than ourselves. Perhaps more than ever before, we might have a need for a de-politicised, neutral space, where we can go to forget our worries and concerns in these troubled times. And it might therefore suit us to view our yoga classes and communities as politically neutral and existing as an alternative to politics. But we also need to recognize that our innate need for community and for simple companionship means that we might also be willing to overlook red flags and subtle signs that could in fact allow us to recognize that the implicit (and almost always unspoken) biases of our particular chosen group do not actually align with values that we personally hold dear. It might mean we are willing to overlook behavior that prevents us from accessing the deeper, ethical practices of yoga to overcome samskara, imprints or impressions left in the deep recesses of the mind by experience (which for all of us is experience rooted in systems of white supremacy, settler-colonialism, and capitalist patriarchy). It might mean we compromise our ethics in ways that make us complicit and which enable abuse and violence to continue.

This overlooking becomes particularly problematic when aligned with the rhetoric of self-care that much of modern yoga culture espouses. (Not to mention that this focus on self-care might not be in line with traditional teachings, but rather an example of yoga culture taking on the dominant values of the society it is embedded within). What do we as practitioners do when something a teacher or prominent member of a community says feels “off” to us? How do we make sense of the dissonance? Most of us, particularly women, are very well-schooled to prioritise social harmony and cohesion over our own internal wellness and wholeness. If we are yoga teachers ourselves, can we say that what we transmit from this space of internalised violence is truly yoga?

As teachers, our careers can be dependent on our reputation, networks and connections, and perhaps we sometimes feel we simply cannot afford to turn down the patronage of a powerful teacher (even if they are known to be abusive, hateful, or someone who engages in victim blaming; or if we suspect that is the case). In such circumstances, we may very well collude with power structures we consider ourselves morally opposed to. In fact, female practitioners might do this most of all. This becomes even more complicated when we consider the material conditions of women working within the yoga industry. Let’s be clear here that this is a world in which employment is increasingly scarce, underpaid, and rarely sustainable past the glory days of Instagram-friendly “health” and desirable bendiness. Rampant self-promotion is necessary and resources (for example students or studio space) are competed for fiercely. In this uncertain industry, it is the working lives of women that bear the brunt. Maternity leave is as likely to be the end of your teaching slot at a studio as it is the beginning of a new chapter of a woman’s relationship with her body. So can we blame female teachers for looking anywhere we can for security?

Misogyny does not always manifest as brutally or obviously as we might think. In our experiences as yoga practitioners, we have seen many apparently innocent incidents which are in fact examples of deeply buried sexism. A great many of the things we take for granted or that are normalised within a yoga class are symptoms of this and other forms of bigotry.

Consider, for instance, how acceptable it is for female practitioners to let their teacher know that they are menstruating, which for all women who do menstruate (whether they know it or not) has an effect on energy levels, joint liability, and emotional states. If this aspect of female embodiment is accepted, how is it made space for within the class? Is an alternative to, say, inversions actually offered? Is that done with a sense that this is not somehow lesser than the “real” work of the class, which is going on somewhere else in some non-bleeding body? What does this do to us as female practitioners? What does it say to us about what it is to have an female body, about yoga? Who loses here, and who gains? How does this play into pre-existing hierarchies of power and of who is given voice?

Let’s take some other common examples of female experiences in yoga. How is pregnancy accommodated? There are many good reasons to attend pregnancy-specific yoga classes–but isn’t there something ironic in the rhetoric of “start where you are” and “yoga is for everybody” that peppers every class if this entirely normal facet of human experience is not accepted by the usual structure of what we are practicing together? What about miscarriage, an experience that one in five to six of known pregnancies ends in, which causes an estimated one in five women who go through it anxiety levels on a par with people who attend psychiatric outpatient services? What about menopause, which every woman who menstruates goes through? These are largely hidden areas of female experience, and perhaps we obscure them further and even complicate our ability to go through them without medicalising or pathologizing them if they cannot be accommodated within yoga.

Once we start looking at these questions, it is difficult to see a yoga class as quite as female-friendly as we might want to think. Is this evidence of deeply-ingrained sexism? Not necessarily–though we, the authors of this article, would argue that it is. At the very least, we might want to re-think our cherished notion of yoga as a non-political space. And we might also want to investigate, at the level of our own practice, how we make sense of the messages we receive from our teachers about what a female body is (and is not), and the way these messages often support essentialist, hetero-patriarchal understandings of a gender binary.

Perhaps we could focus on how it actually feels, somatically, to receive messages both coded and/or explicit, that our body is “less” or “different” than a seemingly “neutral” male one, and how we then pass these messages on to others. As people who are schooled in the rhetoric of “listening to the body”, can we pay subtle attention to what happens to us when we receive disturbing messages from our teachers? What do we do with that dissonance? Do we project it outward onto others, or do we turn it inward? We need to work at this micro-level, as well as at the macro-level, in order to begin to root ot this and other forms of bigotry.

Other practical efforts we can make to combat sexism, misogyny, and patriarchy in yoga:

- At the micro-level, how can we better recognize the way misogyny has become rooted in our preconceptions and understandings of the world? One way to do this is by paying careful attention to our language, with an aim to create more equitable and inclusive social spaces in our everyday lives through a conscious effort to use gender-neutral language. For example, it’s easy to lose count of the times people will use the gendered phrase “you guys” when referring to a group of people, even if every single one of the people in the group is female (or take the use of “man,” “he” as all people, or out in California the use of “dude”). This type of language is what feminist author Kate Swift discusses in her book Words and Women, where “so-called ‘generic’ senses of the word [man] were subconsciously contaminated by the male sense of the word. The result: women were getting lost in our language” (Bodine 1996). Of course this also means those who identify as gender-queer are lost in our language, too.

- When you see a problem, speak up. (And alas, be prepared for push back.) Can’t speak up because it could put you or your job at risk? Perhaps drop an anonymous note to staff with some articles helping educate the studio/teacher on the topic at hand. Seek out other allies who can engage in that conversation with you, or have a friend speak for you anonymously if they are comfortable doing so. Also, consider keeping a written record of incidents and dialogues you have had about such incidents to document any concerns.

- Do your homework on the teachers you are taking classes from. Let’s avoid supporting those who don’t actually walk the walk with any of our money, time, or energy. Find out something disturbing? Let the organization hosting the event know, and consider informing people who might otherwise attend (note: informing others can take many forms from private conversations to public demonstrations).

- Are you a studio owner?

- Consider having a process for anonymous feedback so those who may not feel comfortable disclosing their experiences can do so safely.

- Ensure teachers are properly trained on appropriate conduct, including maintaining professional boundaries with their students–especially when these relationships may be charged with gender, race/ethnicity, and other power dynamics. Have clear policies on how to deal with difficult or disturbing situations that hopefully never come up, but realistically might (like this incident with Eric Shaw demonstrates). This includes having policies and training for all staff (including teachers) on reporting, filing, and addressing disturbing incidents, including those involving hate speech, sexual harassment, or discrimination.

- Have a list of emergency contacts somewhere handy in case emergency situations arise, including mental health services and numbers for local emergency centers. (Sometimes it may also be useful to have this information in a format that can be passed out to others.) Here’s hoping it’s never needed.

- Consider offering classes that can serve as safe spaces of healing for all people, especially marginalized groups. This might entail offering classes or spaces that serve marginalized communities or which can address specific needs for certain groups (things like curvy yoga, classes for people of color, and yes, this might also entail yoga classes for men). Recognize this work is not a marketing gimmick (looking at you Broga!), but rather about building inclusive, empowered, and supported community spaces. The way you teach might need to change to truly serve the community you create (for example, Brandon Copeland’s studio in Washington D.C.).

- Considering offering classes that help fundraise for important causes. These type of events can help build community, establishing connections with local organizations and networks. They can also support those in need, or help raise awareness on important issues. (For example, yoga classes to benefit Planned Parenthood or something like Yoga Refuge’s fundraiser supporting survivors of the Bay Area Ghost Ship Fire.)

- Consider hosting workshops and trainings for staff (and maybe even students) on important topics, including: combatting sexual assault and harassment, trauma informed yoga, anti-racist education, creating spaces that are queer and trans friendly, the impacts of gentrification (which yoga studios are often deeply embroiled in), the nature of privilege, and other forms of anti-oppression education, including feminist education. There are often many local activists and community groups that do these types of trainings you can reach out to.

- Do you run a teacher training?

- Revisit the point above about doing your homework on the teacher trainers you are hiring. Also revisit the point directly above this about types of workshops or trainings that might be important to discuss during a TT.

- Consider the way your curriculum, including book choices, also monetarily supports and legitimates certain instructors. Is it possible to represent a more diverse range of authors in your curriculum (are all the authors of curriculum students read from just one group, such as white people or men)? Can you work in training on trauma sensitivity?

- Have other practical suggestions for us all? Add them in the comments below.

Let’s all work together to create spaces where we can heal in safety and work towards a more socially just and equitable world. Onward and forward!

Co-Contributor: Joanna Johnson has been a yoga practitioner since the 90s, has had a daily practice for fifteen years, and has been teaching for seventeen. She is particularly interested in the myriad experiences of female embodiment. She teaches women’s yoga in a beautiful barn in the English woodland, where her teaching is increasingly inflected with the felt realities of being a householder in intimate contact with the Earth. Her Facebook page is Red Moon Yoga, and she blogs at www.whisperingbodies.wordpress.com.